TAS has been a certified B Corporation since 2013. This means we’re part of a global community of businesses that meet high standards of social and environmental impact.

We recently went through the recertification process and are proud to report that we have been recertified with an impressive score of 147. This marks a significant leap from our 2019 score of 107.3.

In celebration of our latest recertification, we’re reflecting on what it means for TAS to be a B Corp, where we have been, and how we’re working on continuous improvement to “harness the power of business for good”.

What does it mean to be a B Corp?

B Corp Certification means that a company has been verified as meeting B Lab’s high standards for social and environmental impact.

To achieve certification, a company must:

- Demonstrate high social and environmental performance by achieving a B Impact Assessment score of 80 or above and passing B Lab’s risk review.

- Make a legal commitment by changing its corporate governance structure to be accountable to all stakeholders, not just shareholders.

- Exhibit transparency by allowing information about its performance measured against B Lab’s standards to be publicly available on their B Corp profile on B Lab’s website.

The B Corp certification process is rigorous – they don’t make it easy. The process includes an assessment of a company’s activities against a quantifiable grading system for measuring environmental performance, corporate activities, and supply chain transparency.

To maintain certification, companies must undertake the assessment and verification process every three years, demonstrating they are still meeting B Lab’s standards — which are themselves always improving, with continual input from expert stakeholders.

Why did TAS become a B Corp?

As leaders in the impact real estate space, it was important for TAS to become a B Corp business. We recognized that as a B Corp, we can build trust with communities and customers; attract and retain employees and draw mission-aligned investors.

TAS uses the B Corp assessment process to benchmark our performance and identify opportunities to improve our impact according to best practices across all five B Corp dimensions: Workers, Community, Environment, Customers and Governance.

What is a B Impact Assessment Score?

Certified B Corporations must earn at least 80 points on the B Impact Assessment. Scores are verified through a review process, which includes documentation, and phone calls. TAS’s score has fluctuated over the years, from 128.3 in 2013 to 106.6 in 2019.

We’re proud that our 2023 score is the highest score yet at 147. Since our last assessment, we have developed an impact framework and operationalized the framework across our business. We now have dedicated teams working on impact implementation and impact strategy and measurement. We also developed a social procurement program to help us leverage our spending power for good.

What’s Next?

B Corp certification isn’t a destination – our mission to use real estate as a tool to create impact is a constant work in progress. We are always striving to do better, be better, and benefit more communities.

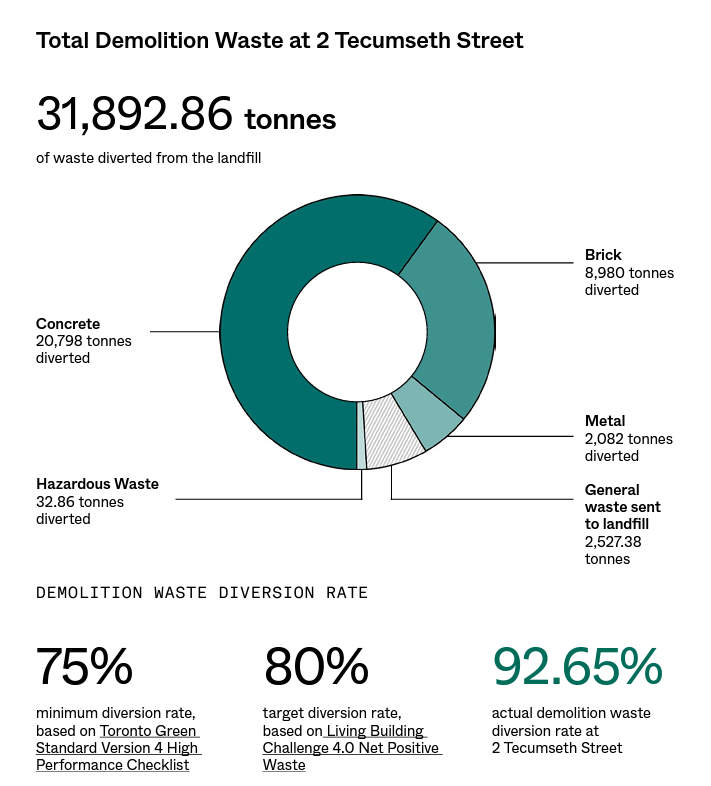

In the last year, we’ve taken some big steps towards longstanding goals, including improving our environmental purchasing program, employee practices and policies, and our commitment to the sustainability of our buildings.

Our next focus is on implementing our Indigenous Truth and Reconciliation Action Plan, and continuing our commitment to climate resilience by integrating the recommendations of IFRS S2 (formally TCFD) across our business.

To us, being a B Corp-certified company is about being part of a global community of businesses working collectively for economic systems change. We know that we must stay committed to this work, move with the world and adapt to meet new needs in order to keep our place in a community of B Corps moving business forward.